Lessons learned from the 2024 season

This blog dives into how I adapted my training routine, set ambitious goals, and used visualization to make every innings count—despite limited practice time. From setting personal records to reaching a long-awaited century, this reflection captures what drives my passion for the game. Whether you're a player yourself or a fan of cricket's mental side, explore how challenges become growth and how, even after years of playing, the thrill of batting never fades.

Marc Ellison

11/9/202411 min read

2024 Season for CSNICC

Team Finish: 8th (out of 10)

Personal Batting Performance: 9th most runs in the NCU; 5th highest average

Key lessons learned:

1. A routine needs to be adaptable

I was only able to attend three team training sessions all season. I managed to get another three 15-minute throw down sessions in outside of that. It was quite a change from my usual routine where I rarely miss a training session and in recent seasons would train on a Wednesday night as well.

With a need to be closer to home in the evenings after the arrival of my fourth child in March, and with many clubs’ paying for video cameras at their home matches to broadcast live on YouTube, I was able to adjust my weekly routine with great success.

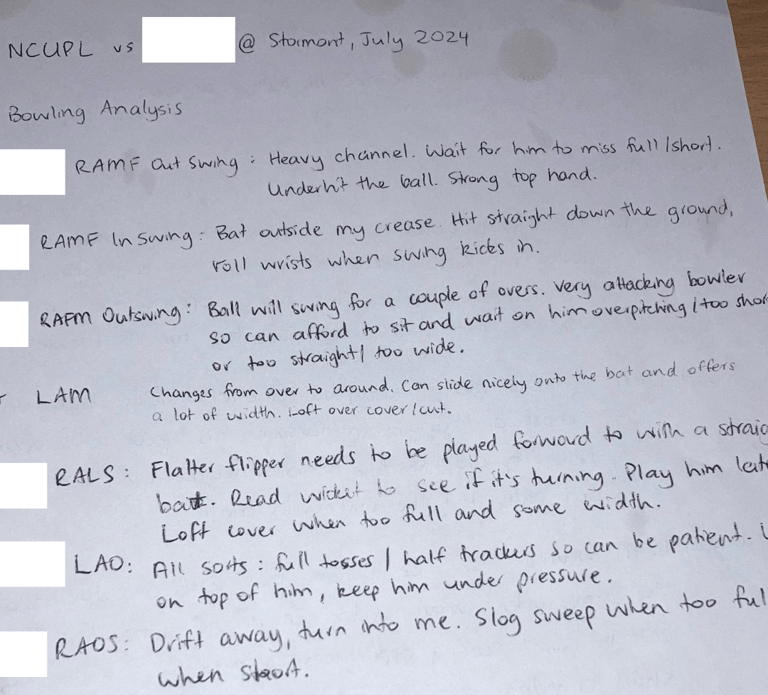

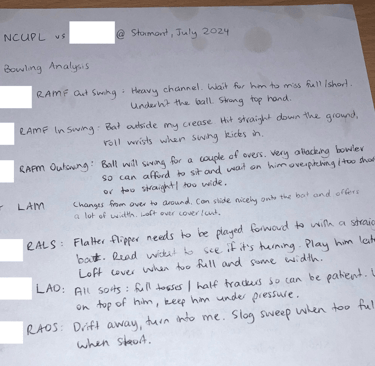

Knowing who we were due to play in the week ahead, I searched for a recent match of theirs on YouTube and studied their bowling attack. I focused on each bowler’s strengths and weaknesses and overlaid that with my own strengths and weaknesses and formulated a plan for how I wanted to play against them and which shots I wanted to score from.

I wrote these insights down on a piece of paper at the start of the week and then spent 10-20 minutes each night visualising the bowler running in and delivering me their best and worst deliveries and, with bat in hand, played out my own best responses.

All of this accumulated mental practice helped me to turn up at the ground on match day feeling comfortable and confident in my ability to handle their best ball and to put their worst ball to the boundary – despite the fact that I hadn’t physically hit any balls during the week.

2. Setting motivational targets enhances focus

At the start of the season, I checked our club records to see how many runs I needed to pass Nigel Jones as our highest run scorer: 1260. Last season, I scored 582 runs, so using that as a guide I thought I’d stretch myself by aiming for 650 each season for the next two.

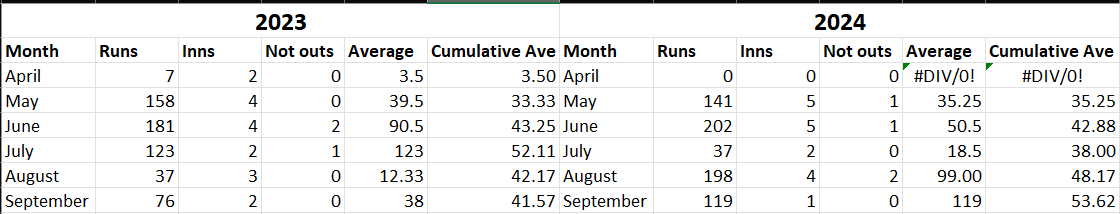

I keep a close track of my performances and broke them down by month to see how I was tracking towards the season goal.

Going into the final game of the season, a dead rubber against CIYMS at Belmont, I needed 72 runs to reach the 650-mark. It was present in the back of my mind as I batted and it was nice to tick that number off. However, while batting, I acknowledged that 72 wasn’t going to suffice and I switched focus towards achieving my first hundred in five years. Once I’d ticked that one off, focus shifted to making my highest score for the club (139*). Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to achieve that one and my day ended on 119. While these little targets are self-centred, I’m acutely aware that the runs I score benefits the team.

I finished the season with 697 runs at an average of more than 53 and a strike rate of 79. I made four 50s and one hundred in 17 innings which meant I was making a fifty-plus score once almost every three innings. I’m pleased with that return, but when I look back at each innings, I can still see I left plenty of runs on the table.

3. The power of visualisation

I first learned how to visualise while at University around 2007, but I didn’t learn its true value until 2011.

Visualising has taken many forms for me over the years; written, imagined, verbal, physical. It’s been a real labour of learning to understand what resonates best at the time.

This season, as I alluded to above, YouTube was a key contributor to helping me understand each bowler’s unique action and what their stock delivery is. Having access to hours of footage was perfect in helping to prepare for my next innings.

It gave me a clear picture of the bowler running in and I was able to imagine how I would respond to each of their deliveries. Initially I visualised the leaves and defensive strokes as well as the attacking strokes, but as the season went on and I became more conscious of the time it was taking to do so, I focused solely on boundary scoring options to each bowler and physically playing those shots after picturing the bowler completing his run up.

It's not something I feel or notice during the process of visualising, but come game day, I experience a sense of calm and understanding as to where I’m scoring against each bowler. Then, it’s just a matter of adjusting to the conditions on the day and match scenarios as they pan out.

It's not until I look back retrospectively at a successful season with the bat, the degree of consistency that I managed (3 single-digit scores in 17 innings) that I realise how helpful the time spent visualising is, particularly given the lack of time I got to hit balls.

In my final innings of the season, I felt fluent. That’s not a feeling I get too often these days. However, given I spent about 15 minutes on 99 as I watched two of my partners get out from the other end, I still had a sense of ease and a confidence that I would get to my hundred. It doesn’t always feel like that.

4. Love of the game goes a long way

In case you haven’t already noticed, I genuinely love batting. I love the uncertainty you feel when you’re driving to the ground in the morning thinking, ‘what is today going to bring?’ I love the moments in the field where I’m trying to understand how the pitch is playing so that I can adjust my approach when it’s my turn to bat. I love being out in the middle and trying to clear my mind and let my instinct take over during those milliseconds after the ball leaves the bowler’s hand.

However, I haven’t always felt like that. It’s been easier to ‘enjoy the process’ since I played my last game for the Northern Knights. There’s something about the fact I’m no longer competing for higher honours that has allowed me to appreciate one innings at a time.

I used to have a constant unease and feeling of dissatisfaction at the fact I was still playing club cricket and not in the professional ranks. I treated every innings as though I HAD to succeed because the selectors would be monitoring my progress. Thinking that my next innings could be the one that made a difference with my career progression.

Inadvertently, I was trying to force the outcomes by focusing on it too much. It’s much harder to play your best when that’s your mentality. You need to live in the moment and play one ball at a time, but that’s much easier said than done.

While I wish I’d was able to harness this approach earlier in my career, I’m also grateful I’ve found it now. Batting is such a punishing art form. One measly error and your day, week or month of batting can be over. That’s not an easy predicament to deal with. Particularly as a young person when you’re still temperamental emotionally.

The skills required to be at your best as a batsman are somewhat paradoxical. You need the mental application, tactical awareness and technical ability of a 40-year-old but the physical prowess and lack of off-field responsibilities of a 20-year-old. Perhaps that’s why so many batsmen find their most productive years around 30.

5. The satisfaction of scoring hundreds never fades

In the final game of the 2024 season, I managed to get the monkey off my back having not scored a century since 2019. 61 innings, 1951 runs, 12 not outs, an average of 39.82 between hundreds. That’s a lot of training sessions. A lot of balls hit. A lot of hours visualising. It always feels worth it when you get there and soak up the moment to celebrate.

7. Self 1 vs Self 2

I re-read the book The Inner Game of Tennis at the start of August. It gave me the reminder I needed to trust my instinct.

The premise of the book is that self 1 is the teller (the ego-mind) and self 2 is the doer (the body). Self 1 most likely does not trust self 2. Self 1 believes it needs to provide instruction to self 2. However, when you consider something as simple as brushing your teeth, does your body require instruction to know what to do? Not once it’s learned the basic actions. It just knows what to do and acts on autopilot.

This is what we need to learn when it comes to batting. Encouraging self 1 to trust self 2 so that self 2 can focus solely on the ball and instinctively react to the ball that is bowled to us. When we do this well, this is the zone.

No thought and promoting from self 1, just simple reacting from self 2. And what a feeling it is.

I experienced it the week after reading the chapter ‘Trusting Self 2’. I was batting in a league fixture against Instonians and I edged one short of the slip cordon in my first over and it ran away for four.

The next over I hit two pull shots for six over square leg as the swing bowler lost his length. They were completely instinctive. The ball hit the middle of the bat and as I watched the ball sail over the boundary rope, my trust in self 2 grew significantly. I raced to 28 off about 18 balls with 4 fours and 2 sixes.

Self 1 must have felt left out at that point because I then remember the thought entering my mind: “You’ve had a good start. You need to make this one count.”

So, instead of continuing to trust self 2 and let it do all the work, I then went into accumulation mode, minimised risk and knocked the ball around for ones and twos.

In the end, I made a mistake running between the wickets and was run out for 57 off 60 balls.

Why did I not continue to trust self 2? A number of times in the past I will curse myself for not going onto a bigger score after a fast start. Now, sometimes the cause of my dismissal is not necessarily self 2’s fault. However, I felt that by minimising risk, I was going to help our team to a bigger total by being the player who others could bat around and build partnerships with.

That early boundary-spree spurred me on over the following weeks and I knew it was possible to get back to that zone of total trust, but it is always easier said than done.

A couple of weeks later, we found ourselves chasing 320. It was a good pitch, the outfield was quick, and there was reward for good strokes. I knew we wouldn’t have to go ballistic to chase the total down, but there was also something about the total that put my nerves on edge and I wasn’t as fluent as I had been in the previous match I mentioned.

There were three short balls offered up by the same bowler I had pulled for six just a few weeks previous and I tried to overhit them and completely mis-timed them. It wasn’t something I was consciously doing, but rather something in my subconscious, a stressor, was impacting my ability to be fluent.

That day, it took me longer to find my groove and I made 34 off 48 balls. I felt I’d batted well and was shocked when I got off the pitch and realised how many balls I’d chewed up. It’s funny how things work out sometimes.

Summary

I’m satisfied with how the 2024 season went from a personal perspective and it’s nice sitting here now in the gloom of autumn looking back and feeling as though I gave myself the best chance of success given all of my responsibilities.

What could I have done better?

My strike rate was 79 across the whole season. That’s between 5-10 runs per 100 balls too slow for my liking. How could I have scored quicker? Two innings cost me in terms of strike rate. 24 off 54 against Newbuildings in the Irish Cup and 34 off 48 against Instonians in the bottom four of the League

In the Newbuildings match, I struggled to rotate the strike against their slow medium pace attack. What I can do better next time is drop and run when I’m lacking rhythm. I need to make sure my partner at the other end knows as well of course.

Against Instonians, as I eluded to above, I was on edge sensing the need to get on with it and as such, lacked rhythm. I was conscious that we were slipping behind the required rate and there was some rain forecasted so wanted to be around 100 for one after 20 overs. I couldn’t find my calm, relaxed state and scored slowly then we needed as a result.

I also need to practice lofting the ball straight down the ground. When I’m at my best, I’m confident in whacking the bowler back over his head. I haven’t practiced this enough and therefore it’s not instinctive.

I’ve found over the years that I score quickest in the last 20 balls of my innings, especially upon passing 100. With that in mind, if I’d have found a way to kick on with the starts against Waringstown (47 off 69), Carrickfergus (70 off 107) and Cliftonville Academy (46 off 65), I know I’d be able to get back up to a run a ball, if not better.

Plenty to work on ahead of next season to make it even more of a success and to hopefully tick off that elusive team trophy.

The moment you pass three figures is full of satisfaction. You’ve achieved one of your key objectives. It’s an opportunity to soak up the appreciation from teammates and supporters on the side-line. It’s a bonus if your friends and family are there. Fortuitously, this time my wife was in attendance along with my four children. They know how much effort I put into my performance so it’s great to share in the moment with them.

I pride myself on making big hundreds; not allowing myself to reach the milestone and then lose concentration but continue on to a larger total. Generally speaking, each 10 runs you score is a little easier than the previous 10. So, when you get to three figures, you need to capitalise on the rhythm you have and now ram home the advantage for the benefit of the team. You’re ‘in’ and seeing the ball clearly and confidence is high, so you’re in a great position to score quickly. It’s the most enjoyable time to bat.

6. Enjoy the process

This has to be one of the most used modern day cliches. However, I’m disappointed that I was never able to truly appreciate this until the last three years.

What is the process?

For me, it begins with reviewing my last innings:

· How I got out

· What was I thinking when I got out?

· Was I fluent in my innings?

· Did I make a technical/tactical/mental error leading to my dismissal?

· Which type of bowler did I get out to?

· How all of these variables compare to my previous dismissals

· Are any trends developing?

I note down 2-3 key aspects I need to remedy eg watch the ball all the way onto the bat, manage a scenario better eg don’t take a risk against that particular bowler, technical improvements required when driving eg I need to play the ball later to maximise power.

Then, during training I’ll set up a scenario that allows me to focus on these:

· Net session vs bowlers: focus solely on watching the ball all the way onto the bat and not let any technical or tactical thoughts interrupt that focus

· Minimise risks: for example when playing spin, I will work on my footwork during training. By focusing on the trajectory of the ball out of the bowler’s hand I can get well forward when the ball is tossed up by leaving my crease or getting deep in my crease when the ball is flatter to pull or cut. When I do this well, I have little need to take other risks.

· Driving technique: get throws from a consistent thrower and focus on hitting the ball directly into the ground off the bat which is a tell-tale sign that I’m hitting the ball late, under my eyes to maximise power.

Other Blogs You Might Like...